The Pauline Conspiracy Pt 1 of 4

Summary

Introduction

This article presents a critical examination of Paul (Saul of Tarsus), arguing that he fundamentally altered the original teachings of Jesus and the Jerusalem Church led by James, Jesus’ brother. It claims Paul’s theology diverged from the early Christian movement, creating a “Christian Doctrine” that was “utterly alien” to Jesus’ message.

Chapter 1: Origin

-

Paul’s Background:

-

Born in Tarsus to a Roman citizen and a Jewish family, Paul was a Hellenistic (Diaspora) Jew, not a Palestinian Jew like Jesus and the Apostles.

-

Claims to have studied under Gamaliel (Acts 22:3), but no evidence proves he was a primary disciple or rabbi.

-

-

Early Persecution of Christians:

-

First appears in Acts 7:58 as a bystander at Stephen’s stoning. Later, he leads violent persecution of Hellenistic Christians (Acts 8:1–3).

-

Acts 9:1–2 describes Paul seeking authority to arrest Christians in Damascus, suggesting he acted with institutional backing (possibly Roman).

-

-

Contradictory Conversion Accounts:

-

Acts 9:3–19: Paul’s companions hear a voice but see nothing; he is blinded and healed by Ananias.

-

Acts 22:9: Companions see light but hear nothing.

-

Acts 26:13–14: Paul alone sees and hears Jesus, with no mention of blindness or Ananias.

-

1 Corinthians 15:3–8: Paul equates his vision to post-resurrection appearances to Peter and James, implying a physical encounter.

-

-

Self-Proclaimed Authority:

-

Paul asserts his apostleship is divinely ordained, independent of the Jerusalem Church (Galatians 1:15–17).

-

Dismisses Ananias’ role, contradicting Acts. Scholars note inconsistencies in his claims.

-

Chapter 2: Destination

-

Discrepancies in Timeline:

-

Acts 9:20–29: Claims Paul preached immediately after conversion.

-

Galatians 1:16–17: Paul states he went to Arabia for three years before visiting Jerusalem.

-

Galatians 2:1: Suggests a 14-year gap before his ministry began.

-

-

Conflict with Authorities:

-

Forced to flee Damascus (2 Corinthians 11:32–33) and Thessalonica (Acts 17:6–10) after inciting riots.

-

Leaves followers to face persecution while escaping himself.

-

-

Oblivion Period:

-

Little is known about Paul’s activities for ~14 years (Galatians 1:21–2:1).

-

Returns to Jerusalem with Barnabas but remains unrecognized by Judean churches.

-

Chapter 3: The Letters

-

Authenticity of Pauline Epistles:

-

Only 8–9 of 13 attributed letters are likely genuine (e.g., 1 Thessalonians, Galatians, Romans).

-

Disputed Letters:

-

2 Thessalonians: Apocalyptic tone, likely pseudonymous.

-

Ephesians: Style/theology differ from Paul’s.

-

Pastoral Epistles (1–2 Timothy, Titus): Hierarchical language contradicts Paul’s earlier egalitarianism.

-

-

-

Opposition from Jerusalem Church:

-

James and the Apostles reject Paul’s gentile mission and laxity toward Mosaic Law (e.g., circumcision).

-

Paul’s theology (e.g., faith over works) clashes with Jesus’ teachings (Matthew 5:17–19).

-

-

Plagiarism and Manipulation:

-

Claims divine revelation for teachings (e.g., Eucharist in 1 Corinthians 11:23) but likely borrowed from oral tradition.

-

Chapter 4: 1 Thessalonians

-

Context:

-

Written ~50 AD after Paul fled Thessalonica, leaving followers to face persecution (Acts 17:1–10).

-

-

Key Themes:

-

Self-Aggrandizement: Calls himself an “apostle” (1 Thessalonians 2:6) despite no commissioning by Jesus.

-

Eschatology: Predicts Jesus’ imminent return (1 Thessalonians 4:13–17), which never occurs.

-

Threats: Warns of God’s wrath for disobeying his teachings (1 Thessalonians 4:8).

-

-

Hypocrisy:

-

Condemns divination (Acts 16:16–18) yet later endorses prophecy (1 Thessalonians 5:19–22).

-

Abandons Barnabas and John Mark (Acts 15:36–40) but later praises Mark (2 Timothy 4:11).

-

Conclusion

The article portrays Paul as a manipulative figure who:

-

Fabricated his apostolic authority.

-

Corrupted Jesus’ teachings to suit his Hellenistic audience.

-

Evaded accountability while leaving followers to suffer.

-

Clashed with the Jerusalem Church, creating a schism in early Christianity.

Final Takeaway: Paul’s legacy is a “theological conspiracy” that replaced the original, Jewish-Christian movement with a Greco-Roman reinterpretation centered on his personal revelations.

Next Parts: The thesis will further analyze Paul’s letters (e.g., Galatians, Corinthians) and his conflict with James and Peter.

Note: The article relies heavily on critical biblical scholarship, highlighting contradictions between Acts and Paul’s letters to challenge traditional Christian narratives.

By A. Victor Garaffa

Part 1: Chapters 1-4

Part 2: Chapters 5-6

Part 3: Chapters 7-9

Part 4: Chapters 10-13 & Bibliography

Introduction

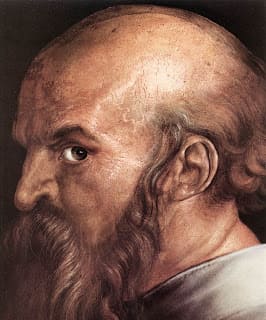

Saul of Tarsus, better known as Saint Paul, has sometimes been a controversial figure in Christianity. The Gospels by themselves would feature as important wisdom literature, but Paul’s Epistles demonstrate the building of the real theology of Christianity. Although some dislike the apparent cultural inflections in the Epistles, without the theology of Saul of Tarsus there is no Christian Doctrine.

In this in-depth scholarly thesis by victor, he systematically analyses the letters of Saul – to set up his ultimate prosecution, and the accusation that Saul of Tarsus did not simply usurp the embryonic Jersusalem Church under Jesus’s brother James, but that he also corrupted the entire original message of Christianity as it was then into something utterly alien.

CHAPTER ONE

Origin

Before we begin to evaluate Paul’s character as it is brought to us by Luke’s, The Acts Of The Apostles, and his own New Testament letters, we should understand his origination and his basic genealogy. Parentage is extremely important to us, for Paul held Roman Citizenship as well as being a Jew by birth, and a Hellenist by theological determination.

It is inevitable then, that for this task we must turn to history, tradition, and Paul’s own words. The latter is the only biblical proof in evidence of his earliest beginnings.

Saul of Tarsus was born a Jew of Jewish parents in the city of Tarsus in Cilicia. His father had achieved Roman citizenship, and Paul inherited that high rank from him. He did not, on any account, earn it himself.

By his own word, Paul was, “…circumcised on the eighth day, of the people of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew born of Hebrews; as to the law a Pharisee…” (Philippians 3:5; RSV)

Paul was a dispersion Jew, not a Palestinian Jew as were Jesus and the disciples. It is important that we understand this, for Paul’s loyalties and practices as a Jew, were far different than the Christ and his Apostles. Paul was a Hellenist or Diaspora Jew, and for these reasons would have been more easily moved toward Christianity. It would also have been a natural evolution for him to theorize about a Gentile mission since he was more familiar with a less orthodox view than Palestinian Judaism. The latter would obviously include Jesus and his disciples.

There is no proof, or tradition, that Paul was a Rabbi although it is probable that he did study toward that goal. Luke indicates that he studied under Gamaliel, in Jerusalem. (Peake’s Commentary on the Bible; Page 873: 763a)

“I am a Jew, born at Tarsus in Cilicia, but brought up in this city at the feet of Gamaliel…” (Acts 22:3; RSV)

The Gamaliel referred to in the scriptures, was the first of the famous rabbis of that name. He was a descendant of Hillel. (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 9: Page 86)

We must be alerted at once that there is no evidence that Paul was the primary or singular student of the famous Rabbi. To say one studied under, or at the feet of, Gamaliel or Hillel or any other great teacher, only meant that he studied in the school of that teacher. There were many students in each of the special rabbinical institutions but it did not mean that that Rabbi or teacher knew them.

Saul of Tarsus was, at this point, a non-descript bystander. What we have of him to this point, is that of his own word.

It is in this city that we first meet the chief character, and subject, of this thesis. It is a time of radical movements within the infant church, sparked by revolutionary figures of which Stephen seems to have been the most outspoken. Stephen appears to have been a teacher, though tradition has it that he was very young. He was a Hellenist, and obviously held to a philosophy that caused great concern to the Synagogue and the leaders of the new Christian religion.

Stephen was probably the most talented of the Hellenistic teachers. (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume7: Page 182) He held that Israel as a kingdom had been unfaithful to its heritage, and that the true Israel was represented by the new church. (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 7: Page 182)

This was a theme that Paul was later to adopt.

The Greek mind, that same Greek mind which had dared to regard its philosophy in a state as high as that of God’s word as given in the Holy Scriptures, now decried the Jewish religion and the Temple. It is interesting to make note of a statement put forth by professional theologians concerning Paul’s relationship with the Law. It is discussed at length later in this work, and brings us a true picture of the man’s character.

Though Stephen repudiated the old Israel, he did not reject the Law itself, which Paul did many years later. (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 7: Page 182) At the end of an enraging, public discourse, Stephen is dragged out before a frenzied crowd, and is stoned to death. Saul of Tarsus first appears in Acts 7:58.

“Then they cast him out of the city, and stoned him; and the witnesses laid down their garments at the feet of a young man named Saul.” (Acts 7:58)

His position in the community is not known, nor his importance to those involved in the stoning of Stephen. No position of authority is given to Paul at this point in the Bible or in tradition, but his enthusiasm in persecuting the Christian Hellenists gives reign to the thought that he was most certainly a vigilante.

“Saul was consenting to his death.” (Acts 8:1; RSV)

“And on that day a great persecution arose against the church in Jerusalem; and they were scattered throughout the region of Judea and Samaria, except the Apostles… But Saul laid waste the church, and entering house after house, he dragged off men and women and committed them to prison.” (Acts 8:1 RSV)

Whatever position Paul held, he most certainly did not act alone. To physically drag people out of their homes and into prison he must have had assistance, and in light of what history will tell us, the beginnings of an organization of no small power.

Saul is never mentioned as having been a member of the Sanhedrin that condemned Stephen. It is only mentioned that he was a member of the Cilician synagogue. Luke only tells us that Paul gave his consent by holding the coats of those physically involved. Theologians read far more into Luke’s statement. (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 9: Page 106)

Regarding Saul’s authority to arrest and imprison the general population, this student would ask to which prison he sent them. Is it possible that Saul acted, not as an outraged Jew, but a Roman citizen? Did he arrest these people for sacrilegious activities or for sedition? We are given no clue, and in fact, even the theologians are puzzled about the area of Saul’s activity.

It is not believed that Paul carried out his work in Jerusalem. The Disciples were not indicted in the persecution, though they preached Jesus as the Christ in the synagogue. Galatians claims that Damascus was the center of Paul’s activity. (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 9; Page 107)

It is, in fact, to that very city that Saul seeks letters of authority to continue his persecution.

“But Saul, still breathing threats and murder against the disciples of the Lord, went to the high priest and asked him for letters to the synagogues at Damascus, so that if he found any belonging to the Way, men or women, he might bring them bound to Jerusalem.” (Acts 9:1-2; RSV)

What occurs next is plunged into controversy, debate, and contradiction. Saul’s conversion leaves much to be explained, and in its several varying forms, especially Saul’s own accounts, lays down the general ‘modus-operands’ of Saul’s entire ministry. It is one of constant contradiction, changes of loyalty, and an ever-growing attention to his own self-importance.

It begins with, Damascus. Saul’s conversion comes in the form of a vision. As set forth in Acts, this is written by a third party, Luke. Did he receive the story from his friend, Paul, or was he a witness? Paul’s own words bring us a sense of his experience and contradiction.

“Now as he journeyed he approached Damascus, and suddenly a light from heaven flashed about him. And he fell to the ground and heard a voice saying to him, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” And he said, “Who are you, Lord?” And he said, “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting; but rise and enter the city, and you will be told what you are to do. The men who were traveling with him stood speechless, hearing the voice but seeing no one.” (Acts 9:3-19; RSV)

Blinded by the light that he alone can see, Paul is sent to meet, Ananias. This disciple is to tell him of his mission and to heal Paul of his affliction.

These are purported to be Paul’s words as spoken to Luke. Paul offers witnesses, not by name, but by inference; “the men who were traveling with him.” The men are not named, we do not know who they might have been. They see nothing, but hear the voice.

We may assume many things, but can prove nothing. Chief among our objections to this report is clear. In the event of such an occurrence, including Jesus’ several experiences, witnesses are necessary.

Even in Jesus’ baptism there are witnesses, John the Baptist and his disciples, which group included Andrew. There were also three ‘named’ witnesses to the transfiguration. Throughout the history of the Bible, witnesses are provided who are named, and with whom we are familiar in the course of these events. Even Aaron is made part and party to the mission of Moses, spoken to by God and given the very words of God, (Exodus 4:15-16; RSV) as Moses received them in his vision of the burning bush. (Exodus 4:27-28)

Later, Paul speaks again through Luke, and the vision experience changes.

“Now those who were with me saw the light but did not hear the voice of the one who was speaking to me.” (Acts 22:9-13; RSV)

This time the witnesses hear no voice but they see the light. Oddly enough, they are not blinded as Paul is reported to have been. The statement is, however, absolute and it contradicts Paul’s previous account. Here again, Paul is sent to Ananias to receive his ‘calling’ and a restoration of his sight.

Later still, when Paul addresses King Agrippa, the witnesses hear nothing, they see nothing. and the vision becomes Paul’s alone.

“At midday, O King, I saw on the way a light from heaven, brighter than the sun, shining round me and those who journeyed with me. And when we had all fallen to the ground, I heard a voice saying to me in the Hebrew language…” (Acts 26:13-14; RSV)

Hebrew, or Aramaic? It is irrelevant except to note that not only has this addition been made to the vision, but now the voice tells Paul what his task is to be. Ananias is forgotten, and nowhere does Paul state that he was blinded. Added also is the fact that this time, Paul claims that he sees the speaker.

In the other renditions Paul gives of his vision, he is told to go into the city and there he will, “… be told all that is appointed for you to do.” (Acts 22:10-11; RSV)

It is of importance to note once more, in the previous version (Acts 26:16-18; RSV) of Paul’s testimony there is no mention of his blindness, or of Ananias. In the end, we are to observe by his own words that Paul’s recovery from blindness did not involve a perfect ‘healing’. His own words testify to the fact that his sight-impairment was permanent and so he complained of it throughout his travels. At the last, he claims that his ‘thorn in the side, is of Satan. It would also appear that there was some matter of his being disfigured, unsightly to behold.

So the vision changes, subtly, but enough so that at the end Paul becomes the main character. He sees the great light enveloping himself and those around him, he hears the voice, and through it, he believes that he has been given a calling to minister to the Gentiles. Luke openly declares that Paul began at once to “… declare to those at Damascus, then at Jerusalem and throughout all the country of Judea, and also to the Gentiles…” (Acts 19:20)

In this, he also contradicts Luke, bringing doubt on his word.

The good physician has all this beginning at the moment of Paul’s ‘vision’, but in fact, none of it occurred for years. In the other versions, it is Ananias who heals Paul and tells him what his mission is to be. In this there is no mission to the Gentiles, unless Paul himself decided that Ananias’ words were to be interpreted in that manner. Surely Jesus, in his lifetime, adjured the Apostles to avoid the Gentiles and the Samaritans.

“… for you will be a witness for him to all men of what you have seen and heard.” (Acts 22:15; RSV)

But there is one other situation in which Paul calls up the vision that eventually caused his ‘conversion’, and this time it is also in his own words. One must note carefully Paul’s choice of words, for they seem to camouflage the difference between that which others saw, and that which Paul experienced. He wants it to seem as though the events are the same, bearing the same substance, but they were not. Paul mentions it in connection with the appearances of the risen Jesus after his resurrection from the dead.

“For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received, that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures, and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. Then he appeared to more than five hundred brethren at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have fallen asleep. Then he appeared to James, then to all the Apostles. Last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared also to me.” (1 Corinthians 15:3-8)

Make note that Paul ignores what later appears in the Gospel stories which tell us that the women were the first to see the living Jesus, not Peter. Surely he had knowledge of the oral tradition concerning these events. More enlightening is the fact that Paul seems to be making another, revised statement concerning his vision.

Those who saw Jesus at the times Paul indicates, beheld the living, in the flesh, Jesus of Nazareth. Paul’s vision seems to be taking on flesh and bone of its own. He is most certainly insinuating that he was confronted by the living Jesus, when in two accounts of the event he sees only a light and hears a voice. In the third, where the healing of his sight and Ananias’ instructions disappear, Paul claims to see Jesus, in the flesh, as he speaks to him.

It is upon this new tale that Paul bases his authority, contending that his ‘calling’ is the same as that of the Twelve, who were personally chosen by the living Christ, and that of James, Jesus’ brother.

Was he building a case for the future with which to defend attacks against his own self-proclaimed apostleship? Or was the event so monumental that Paul’s ability to function was becoming impaired. Was Festus correct? That which the church has taken as a slander against Paul’s character, may well have been an accurate assessment.

“And as he thus made his defense, Festus said with a loud voice, “Paul, you are mad; your great learning is turning you mad.” (Acts 26:24; RSV)

In regard to Paul’s words, suspicion is raised and is not easily removed. Paul has attempted to set up an argument that no one can assail. It is his word against the world; no witnesses, no proof provided, and in Paul’s mind none is needed. However, even professional theologians must offer their own explanation.

Professional theologians agree that Paul regarded his own experience with Christ near Damascus as being essentially the same as that of Cephas and James, to whom the resurrected Jesus had appeared. Of course, they also agree that no one can be certain of this. (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 7: Page 191)(Peake’s Commentary on the Bible; Page 873: 763b)

No one can say? No one can argue against a statement that infers God’s direct intervention in a matter. One may say that they ‘saw’ anything they wish when a spiritual agent is involved, without fear of contradiction. But in the end, their own actions, their own words, provide us with the truth.

“But when he who set me apart before I was born, and had called me through his grace, was pleased to reveal his Son to me, in order that I might preach among the Gentiles, I did not confer with flesh and blood, nor did I go up to Jerusalem to those who were (A)apostles before me…” (Galatians 1:15-17; RSV)

This statement is extremely important, for it will contradict Luke again when the visit, according to Paul, includes the Apostles extending him, “…the right hand of fellowship. (Galatians 2:9)

Oh, how Paul’s authority is to grow, even to the point of claiming that he is Nazarite!

Paul’s account in (Gal. 1:1), is given in the context of an argument over the nature of his apostleship. In order to valid his claim, he says that his call is free of all human authority. This includes the leaders of the Church at Jerusalem. He ignores Ananias completely, thereby erasing his place in the ‘vision’ story, and in doing so, he refutes Luke’s account, which may well have been derived from Paul’s own words at the time.

But this is the manner in which Paul operated, this was the manner in which he treated people who were not absolutely necessary to him. If God called Paul, he also called Ananias, not only for his ‘healing’, but also to instruct Paul in his new role. Paul chooses to disregard him as unnecessary.

At the writing of Galatians, Paul’s authority has grown beyond measure. He is now an ‘apostle’, and he proclaims his standing as, Nazarite, one chosen before his birth as a Prophet of God. No one may challenge his position, no one may challenge his authority, Paul has taken it beyond the realm of man into an arena which no one dare question. Yet God, the eternal Father, demands that we challenge it.

Paul’s only defense is to say that all of his claims are beyond ‘flesh and blood’, so it matters not what any one says including the Twelve, including Jesus’ brother James, including the Elders of the Jerusalem Church. This is the argument of one who does not dare to defend his statement, but one who wishes to avoid any coherent debate of his position by the simplest means possible. God did it, therefore there can be no discussion.

Paul’s claims are so insidious, that he has written authorities in our own time, contradicting themselves. (Peake’s Commentary on the Bible: Page 974: 851e: (Galatians 1:15-16))

But as the same source has already commented, “That Paul saw Jesus in the flesh we cannot say.” Indeed, the variations and inconsistencies in Paul’s narrative concerning his ‘vision’ cause one to hesitate in accepting it at face value. One can easily see that it has grown with the telling.

And here, still in the presence of Festus, Bernice, and King Agrippa, another matter must be brought to our attention. It concerns Paul’s supposed imprisonment.

He was not actually a prisoner, not locked in chains within a cell and left to suffer. In fact, as we will discuss later, he was under house arrest at his own bidding and free to move about and have visitors. His journeys continued, but this time at the expense of the Romans and not his congregations. This is attested to by Felix and then King Agrippa himself.

“But Felix, having a rather accurate knowledge of the Way, put them off, saying, “When Lys’ias the tribune comes down, I will decide your case.” Then he gave orders to the centurion that he should be kept in custody but should have some liberty, and that none of his friends should be prevented from attending to his needs.” (Revised Standard Version; Acts 24:22-23)

“And Agrippa said to Festus, “This man could have been set free if he had not appealed to Caesar.” (Revised Standard Version; Acts 26:32)

Paul constantly uses his ‘imprisonment’ to draw sympathy and attention to himself, but we shall see, at the proper time, that Paul was absolutely overjoyed at the circumstances he himself had created. Now he was free to preach to the soldiers and spread his gospel among them, something that might never have happened otherwise.

And why ask for Roman assistance to start with? Not from preaching the gospel, but Paul sought protection to save his own neck from a riot that he himself had caused. But more of this will be revealed later.

It must also be remembered that Saul of Tarsus, by his own admission, in his own words, was guilty of two murders.

CHAPTER TWO

Destination

It is here that we are met by inconsistency once again, only this time it is caused by the discrepancies in ‘biblical history’. Paul’s letters and the book of Acts disagree in important aspects, and it is Luke’s narrative that comes into question.

Even in our own studies, Paul creates controversy. Scholars are forced to choose which writing is legitimate, and in this case they must choose Galatians. The Interpreter’s Bible puts it as eloquently as is possible in a situation like this. (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 9: Page 126)

It is unfortunate that one writing must be set against another, especially so when one is authored by the writer of a synoptic gospel, Luke. If his facts were ‘disoriented’ when involving a personal friend whom he accompanied on many journeys, how far afield from the truth must his third hand essay of Jesus be? More so when Paul’s honesty is to come under close scrutiny later in this thesis. This is no trivial matter.

The beginning of Paul’s activities, according to Acts, begins almost simultaneously with his conversion, but Paul’s own account of events as written in Galatians, disagrees completely with Luke’s.

As we read of Paul’s activities in, Acts 9:20-29; 11:29-30; 15:1-29 or in Gal. 1:15-2:10, two very different pictures are presented, for Luke’s writing refuses to accept the element of time and its passage. (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 9: Page 10)

We are told repeatedly, by both Paul and his later interpreter’s, that he did not go up to Jerusalem until three years after his conversion. And in fact, Paul’s public ministry did not begin after that short visit, but at least fourteen years later. In the end, seventeen to twenty years pass into obscurity before we hear from Saul of Tarsus again.

But allow us to digress for the moment to fully explore this area of the New Testament. When discussing the events following Saul’s conversion, Acts must be examined against Paul’s own written word.

“For several days he was with the disciples at Damascus. And in the synagogues immediately he proclaimed Jesus…” (Acts 9:19-20; RSV)

“…I did not confer with flesh and blood, nor did I go up to Jerusalem to those who were (A)apostles before me, but I went into Arabia…” (Galatians 1:16-17; RSV)

The contradictions are obvious, and are best stated by, The Interpreter’s Bible. Paul says that after his conversion he, “…went away into Arabia” (Gal. 1:17). Acts indicates that he began preaching at once. If nothing else, Luke’s account is historically incorrect. (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 9: Page 125)

The noted gospel writer comes under fire by his ‘presumed’ close friend’s written word. Luke seems to complicate matters by having the Jews of Damascus try to kill Paul in that city. Then, as though to compress time, he has Paul arrive in Jerusalem to join the disciples. But Paul is turned away. (Acts 9:23-26; KJV; RSV)

Paul states that it was three years before he went to Jerusalem. Luke has cut this to a matter of days. Luke indicates that Paul was turned away by the disciples in Jerusalem because they feared him. According to Paul, this is not true.

Paul swears that he was only in Jerusalem for fifteen days, and that the only Apostle he saw were Peter and James the Lord’s brother. (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 9: Page 125)

“Then after three years I went up to Jerusalem to visit Cephas, and remained with him fifteen days. But I saw none of the other Apostles except James the Lord’s brother. (In what I am writing you, before God, I do not lie!)” (Galatians 1:18-20)

The fact that Paul is so adamant about what he has said, in fact swearing an oath that he is telling the truth, would force us to consider that he may well have been defending himself against someone else’s statement concerning the event. By swearing an oath in the matter we must also question why Paul would be so determined in denying a simple meeting with the disciples. If it is the first time we see this in evidence, it will not be the last.

Luke also tells us that Paul, “…preached boldly in the name of the Lord.” But this is contradicted by Galatians.” (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 9; Page 125)

Though Paul went into Arabia, there is no suggestion as to how long he was permitted to stay in that country. Being forced to leave, he went to Damascus, and then after three years, went to Jerusalem. But why was Paul compelled to escape over the city wall? If theologians indicate that his preaching in the synagogues in Damascus was highly unlikely, it would have been even more improbable that he did so in King Aretas’ presence.

In fact, it was King Aretas, King of the Arabias, and not the Jews who tried to have Paul killed. The reason is unknown to this day, but Luke would have us believe that it was due to Paul’s preaching. So what is the truth of this matter?

Paul was always getting into trouble with authority figures, including the Disciples, and his stay in Arabia was probably very short. King Aretas IV, king of the Nabataens, reigned from 9 BC to 40 AD. For some reason, Paul angered Aretas and was forced to return to Damascus. It is doubtful, considering the time element and the circumstances, that it had anything to do with preaching the Gospel. (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 10: Page459-460)

“At Damascus, the governor under King Aretas guarded the city of Damascus in order to seize me, but I was let down in a basket through a window in the wall, and escaped his hands.” (II Corinthians 11:32-33; RSV)

Paul does not tell us why he was pursued, and only pure conjecture would dare to assume that it was due to his preaching. It has been indicated by experts that it was highly unlikely at such an early period in Paul’s life. Beside the information given to us by theologians, we must also remember that it would be another fourteen years before Paul’s public ministry began.

Wherever he lingered, it was at this point that Paul retreated to Jerusalem. Looking at this matter with the advantage of having a fairly complete picture of Paul’s ‘problems’, he may well have had nowhere else to go but to the Apostles. It would seem that he had few if any choices.

At this point other opinions must be brought into the discussion, but it seems that major translators and theologians find our argument of some value.

It is doubtful that Paul was aware of any gentile mission at this time, and professional theologians agree with this conclusion. The next thirteen or fourteen years after the event on the Damascus road is a matter for conjecture. At that point he went to Arabia (the Nabataen kingdom). We cannot begin to suggest that he began his ‘ministry’ at this point in time. (Peake’s Commentary on the Bible; Page 874: 764a)

There is also agreement that it was three years after his conversion that he went to Jerusalem. The visit was certainly not by invitation because the Jewish Christians were still terrified of Paul. Years later it would take the sponsorship of Barnabas to bring him to that city and the Jerusalem Church. The first visit, by all accounts including Paul’s, was short and involved a private meeting between Peter, James, and himself. (Galatians 1:18; RSV)

At this point, Paul sinks into oblivion. He is gone into regions which might have included his home of Tarsus in Turkey, and there it is possible that he stayed in the territories of Cilicia and Syria.

“Then I went into the regions of Syria and Celicia… Then after fourteen years I went up again to Jerusalem with Barnabas…” (Galatians 1:21-2:1; RSV)

By Paul’s own admission he was still unknown, “…by sight to the churches of Christ in Judea.” This statement is made in Galatians 1:22, indicating that he was still not actively preaching ‘in the world’.

But events were taking place, and as was usual, Paul’s ego was acting in direct opposition to good sense. This method of operation, as already noted, left Paul in a constant ‘escape’ mode. More unfortunately, it left those who were innocent bystanders to suffer the punishment better deserved by Paul himself. On more than one occasion, Paul escaped problems he had started, and left his so-called congregations to face the anger of civil and religious authorities.

“…And he spoke and disputed against the Hellenists; but they were seeking to kill him. And when the brethren knew it, they brought him down to Caesarea, and sent him off to Tarsus.” (Acts 9:29-30; RSV)

Ac. 9:26-29 also argues against any Gentile mission before this time. (Peake’s Commentary on the Bible; Page 874: 764a)

Peake’s Commentary on the Bible, makes a telling statement about this lengthy period in Paul’s life. It would appear to agree with the conclusions drawn by this student and the very word of Acts 9:30; Galatians 1:21, 2:1. The statement this volume makes is definite.

“Of these years we know nothing.” (Peake’s Commentary on the Bible; Page 874: 764b)

CHAPTER THREE

The Letters

The journeys of Paul are covered, historically, by Acts. Volumes have been written with Luke’s chronologically arranged narrative as their guide, and with the assistance of Paul’s comments in his own letters. In some instances they speak of Paul’s intentions to travel to specific locations, but those intended visits were often thwarted by men and circumstances.

Between the two, however, the tale of his missionary adventures is well covered. Therefore, it is not necessary for this treatise to go over the identical soil again, but rather to study the letters he wrote in an extremely thorough manner. It is not Paul’s journeys that will reveal the man to us. There is no question as to his many ordeals throughout the Middle East and Europe, adventures that rival any of modern day, but his writings will evidence the motives behind his many pilgrimages.

In this study, we must also include those letters which we know are not Paul’s, and which testify to views that opposed those of his personal theology. We must include passages from Jesus’ teachings which Paul’s own thoughts and actions seem to contradict.

Within the context of this thesis, it would be wise to remember that the Gospels we are so familiar with, did not exist in written form until very late in Paul’s lifetime. Those sayings or deeds of Jesus that Paul mentions, predate the written Gospels, and in several instances, influence them.

An excellent example is Paul’s account of the Eucharist in 1 Corinthians 11:23. This is the oldest record of that event that has come down to us, and we will learn later that it is Paul’s influence that reflects in the Gospels. (Peake’s Commentary on the Bible; Page 927: 804f)

It would also be proper to keep in mind that the Apostles were already practicing the ‘common’ meal, and in essence, the ‘Passover meal’, in remembrance of that last meal with their Lord. In practice, the Jerusalem Church honored Jesus’ instructions at the time of the last supper. There was no meal or sacrament commemorating Jesus’ death among the disciple’s congregation.

From the outset the congregation formed by the Apostles observed baptism and the Common Meal, but it was natural that those who had celebrated the Passover with him should remember the meal during which he had bidden them farewell. (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 7: Page 180)

The information that Paul had concerning the life and teachings of Jesus, who was called the Christ, had to have come from third party information, an oral tradition that might have existed in Jerusalem, and the teachings of the Twelve which had been carried to areas in the middle-east by themselves and their own disciples.

Paul writes that he had received the custom, “…from the Lord.” It is obvious that he had not been present at the Last Supper, so what is Paul insinuating? The Interpreter’s Bible, openly disagrees with those who take his words to mean that he received this ‘sacrament’ in a vision from the risen Christ. (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 10: Page 135)

Of personal knowledge of Jesus, Paul had none! The philosophies and theologies that he created were of his own conception, and those colored by his education as a Pharisee in a Hellenistic world, and the pagan religions which surrounded him. His own writings evidence these influences.

Paul often added to simple messages, complicating them with his own theological theories. In was part of his literary method of operation. (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 7: Page 21. IV)

With this in mind, we must search the world of the theologian and historian who have, by their own devices, attempted to catalog the writings of Paul in their proper chronological order.

Within the context of the New Testament, there are thirteen letters which were originally attributed to Paul. Through modern research, and the development of literary examination, only eight of these works can be directly attributed to his mission to the Gentiles, nine if we consider Ephesians, which is more than likely pseudononimus.

In the most widely accepted chronological order they are as follows:

1 Thessalonians 49-50 AD

1 Corinthians 54-55 AD

Galatians 54-55 AD

II Corinthians 55 AD

Romans 56 AD

Colossians 59-61 AD

Philemon 59-61 AD

Philippians 59-61 AD

Questions concerning II Thessalonians, would bring doubt as to Paul’s authorship. The eschatology is way off and there is also a prophecy of the advent of Evil. The anti-Christ who has all power evidences an ‘anti-religion’ theme rather than an ‘anti-Christian’ motif. It is certainly not Pauline.

The Interpreter’s Bible, reveals the thinking of professional researchers and their reasons for believing this second letter must be a later writing and not an authentic letter of Paul’s or anyone in his group. It is not only the theology that is in question, but the style and tone of II Thessalonians which form a basis for evidence against it being Paul’s. (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 11: Page 250)

Even Peake’s Commentary on the Bible, takes into consideration the question of authenticity, noting that the challenge has grown as time passes. One of the biggest concerns is the apocalyptic nature of this second letter, most assuredly not Paul’s usual style. It is firmly believed that the letter is an imitation. (Peake’s Commentary on the Bible; Page 996: 869e; Authenticity)

The question of Paul’s hand is also the case with, Ephesians.

A growing number of scholars now believe that the epistle is pseudonymous, but it must also be noted that this feeling is not unanimous; a number of excellent critics are not convinced that the letter is not Paul’s. (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 10: Page 597)

It was not uncommon for writers to use the name of well-known figures in order to bring importance to their own works, or to plagiarize the works of others. It is also possible that this may be the work of a member of Paul’s staff to whom he dictated a letter at an earlier moment. Several of the letters attributed to Paul were written by others for he certainly dictated several of them to ‘scribes’. From what we can learn from Paul’s own words, his eyesight never recovered sufficiently to allow him the ability to proceed with many such tasks on his own.

Evidently, as already pointed out, the healing he speaks of connected with his conversion ‘vision’ was an imperfect one, or is another of his fabrications. (Peake’s Commentary on the Bible; Page 928: 805b)

We must then consider the letters titled, James and Hebrews. They are most certainly not Paul’s. The letter of James, is not only a direct contradiction of Paul’s theology of, ‘salvation based on faith alone’, but an assault and challenge to that theology.

Hebrews, calls up the vision of Jesus being descended of the priesthood, in fact, the priesthood of Melchizedeck. And the writer goes so far as to consider Jesus, a Son of God, and not the Son of God. (Hebrews 5:8-9; RSV)

The author is unknown, but this letter is written in the ‘high’ Greek, and brings to mind the descendency through Mary and her blood relationship to Elizabeth, who was descended from the High Priesthood of Aaron.

Here, Peake’s Commentary, speaks without hesitation. “…it can in no sense be regarded as a Pauline document…” (Peake’s Commentary on the Bible; Page 927: 804f)

The writer of Hebrews, obviously calls up a knowledge that extent New Testament scripture has either deleted, ignored, or has conveniently forgotten. At any rate, it is a proper parallel to draw for the Messenger of God.

These writings are not consistent with Paul’s line of thought, nor are they in his style. Without question, they would refute that which he has preached. Although we do not have other writings to call upon, there are attacks upon Paul’s use of titles and authority to which he himself alludes.

Professionals voice the opinion that Paul’s assailants are unknown. They are shadowy figures that try to destroy his work. This student, however, believes that they are the Disciples, who disagree with Paul’s actions. It is easy to see why they hound him so relentlessly, for Paul continued to assume titles and authority that were not his. In fact, it is noted that Paul, “…was not of the sort to brood over his wounds.” Yet his letters continually wail about his physical ailments and his imagined persecution by the Judiazers. (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 7: Page 201)

The effort of this theologian to coerce our minds toward mystifying enemies, is fruitless. Paul makes it obvious that the Judiazers were no less than Christ’s Apostles. Why they, ‘…hounded him so relentlessly…’ becomes obvious when the facts are presented. But the statement that, “Paul was not of the sort to brood over his wounds…” it is an absolute aberration, Paul does nothing less!

It is sufficient to indicate that, as usual with him, he managed to stir the anger and resentment of those most high in the organization of the Jerusalem Church and its followers. It was the Twelve, including Jesus’ brother, James, of whom he was most jealous. Could he have been preaching a gospel that was completely out of line with the truth they had lived?

Could it have been the Apostles and their followers who continually denounced Paul for embracing a commission to which he had no rightful claim, and for ministering to a false gospel? Even if it were, theologians most assuredly would not dare to implicate the Twelve. They would not dare force the world’s congregations to make a choice between Paul and the Twelve. What then? Incriminate someone else, the unnamed, unidentified, Judiazers.

With these matters stirring the imagination, we begin an intense examination of the writings of one called, Saul of Tarsus.

CHAPTER FOUR

I Thessalonians

Our study of the Epistles begins with an old story repeated once again. Paul has come to Thessalonica after a bitter and painful experience at Philippi. What the exact details are, at this point in his writings, we do not know. Paul gives us no indication as to what had occurred, or what brought about his terrible treatment in that city. Sometimes, silence can indicate more than words.

Paul makes no reference to his misfortune having come from preaching a gospel about Jesus of Nazareth. In the same manner, King Aretas tried to have him captured and put to death for some unknown trespass. Theologians only assume that it was due to his preaching, for Paul remains silent. If that premise had been true, keeping in mind the manner in which Paul always boasted about sermonizing his gospel, he would not have hesitated to make the point once again.

But one might as easily conjecture that the missionary’s egoistic attitude and his self-proclaimed importance, as authoritative and insulting as it will prove out to have been, caused him more problems than anything else.

It is obvious from works other than Paul’s, that the authorities were still-hunting down the followers of Jesus for sedition and not for religious reasons. This is made plain from the report we have concerning Jason, and the authorities in Thessalonica. The trouble was started by Paul.

Paul had preached to the Jews, with some success among the Jews and Gentile believers. Acts suggests that the Jews, aroused with resentment, organized a riot during which Paul and Silvanus hurriedly left the city. This violent action caused trouble with the civil authorities and made it necessary for Paul to bring his crusade to an abrupt end and move to Beroea. (Peake’s Commentary on the Bible; Page 996: 869b)

“…they dragged Jason and some of the brethren before the city authorities… and they are all acting against the decrees of Caesar, saying that there is another king, Jesus.” (Acts 17: 6-7; RSV)

Luke states that the Jews could not find Paul so, “…they dragged Jason and some of the brethren before the city authorities, crying, “These men who have turned the world upside down have come here also, and Jason has received them; and they are all acting against the decrees of Caesar, saying that there is another king, Jesus.” (Acts 17:6-7 RSV)

Paul left the Thessalonian Christians to suffer at the hands of their own countrymen. (Peake’s Commentary on the Bible; Page 912: 794e)

As soon as there was any indication that trouble was headed their way, Paul and his associates manage to escape the predicament.

“The brethren immediately sent Paul and Silas away by night to Beroea.” (Acts 17:10; RSV)

Once again, Paul is aided in a stealthy escape, leaving those he called ‘brethren’ behind to suffer the direct affront of the civil authorities. Such was the case in the Arabias, and in Damascus. The instigator manages to slip away from the punishment suffered by his followers. In this scenario, Peake’s Commentary also agrees. They suggest that the missionaries may have appealed to the pagan population. This may also have terminated in trouble with the civil authorities, as described in Acts, which forced Paul to bring his campaign to an abrupt end and flee to Beroea. (Peake’s Commentary on the Bible; Page 996: 869b)

This is not the first, or the last, time Paul would leave others to pay the price for his actions. Anxiety finally irritates Paul’s conscience, but he is still above the problems he has caused others. Let it suffice to say that Paul was not always to be a free man, but even that device was by his own invention.

From here, Paul proceeded to Athens alone and then to Corinth. In a depressed state of mind and in ill health after his failure at Athens, we finally see evidence of some anxiety on Paul’s part concerning the state of affairs in which he left the brethren in Thessalonica. Timothy is sent to investigate the situation.

Paul’s anxiety over Thessalonica prompts him to call Timothy from Beroea to Athens (Acts. 17:15). He was sent to Thessalonica (1Thesslonicans 3:1) to find out how Jason and the others were doing in face of, “…official opposition…” (Peake’s Commentary on the Bible; Page 996: 869c)

Here, our professional friends are kind enough to consider the problem that Paul caused as, ‘official opposition’.

Upon the return of Timothy and Silvanus, with a report that the brethren have not only survived attacks by the authorities and the Jews but are doing well, Paul writes to the church at Thessalonica. The letter most probably dates to 50 A.D. There is obvious relief in the tone of this writing, and we begin our study of that letter with this short history in mind.

Paul introduces himself and his two fellow missionaries, Silvanus and Timothy. At this point, Barnabas, Paul’s sponsor and chief agent in the beginnings of the church at Antioch, is no longer with Paul. He has been replaced by Silvanus, after carrying the major portion of the work in Corinth, Iconium, and Lystra. But it is not unusual for Paul to ‘rid’ himself of those who might bring question upon that which he considers to be his own work, as well as inquiries concerning his authority, as we will see.

The honest scholar must remember that it was Barnabas who, at a most opportune moment, expressed faith in Paul, was successful in bringing him before the several disciples, and started him in his lifework. That, of course, did not begin for another fourteen years after this first meeting in Jerusalem. Barnabas was held in the highest esteem by the Apostles, who gave him a new name, “Barnabas, son of encouragement.” He constantly discovered and educated others who overshadowed him, as proven by his selection of Paul and John Mark.” (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 10: Page 468)

Now, Barnabas is cast aside, Silas takes his place, and Paul takes credit for mentor’s work in Corinth, Iconium, and Lystra.

This is reported in Acts 4:36; 13:1; 1 Corinthians 12:28. Timothy is also chosen to take John Mark’s place, who left Paul for reasons which will shortly be revealed. (Acts 13:5c; 15:37-38; 17:15) (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 11: Page 254)

Paul’s character would never permit another to be known in this light, for it immediately cast doubt on the claim that his authority and his call did not come from mortal men! Especially with Barnabas’ work in Antioch, Corinth, Iconium, and Lystra, and being widely renowned throughout the Jerusalem Church.

But why did John Mark choose not to continue his journey with Paul?

“And after some days Paul said to Barnabas, “Come, let us return and visit the brethren in every city where we proclaimed the word of the Lord, and see how they are.” And Barnabas wanted to take with them John called Mark. But Paul thought best not to take with them one who had withdrawn from them in Pamphylia, and had not gone with them to the work. And there was a sharp contention, so that they separated from each other; Barnabas took Mark with him and sailed away to Cyprus, but Paul chose Silas and departed…” (Acts 15:36-40; RSV) (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 9: Page 208)

Though not known for certain, this student believes that Mark saw what Paul was about, his manner and his method, and disapproving, separated himself from the man.

After all of his hard work in establishing four churches which Paul later takes credit for, Barnabas is suddenly gone from the remaining epic. We will never know the true story since the author of this narrative is the one who caused the removal of these two missionaries much as he erased the place of Ananias in the story of his ‘conversion vision’.

Stranger still, while under continuing protective custody and toward the end of his life, Paul asks specifically for John Mark, claiming that he is very useful in serving him. (II Timothy 4:11) This is something of a discrepancy.

We must also make mention of Paul’s use of the proper name, Jesus Christ, and we are told that he meant it as such! The name, as used by Paul, appears ten times. It is, obviously, a phrase coined by Paul of which we see much as his theologies grow. ( Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 10: Page 19)

It is, in fact, an improper name for, Jesus who is called the Christ; who is God’s Messiah.. It was coined and used by Paul regardless of the fact that it was incorrect. That it has become a common term within the bounds of Christianity, is only one small example of the effect this individual has on our modern theological practices.

“For we know, brethren beloved by God, that he has chosen you; for our gospel came to you not only in the word, but also in power and in the Holy Spirit and with full conviction.” (1 Thessalonians 1:4-5; RSV)

Paul’s obsession with his own person, his own authority, his own gospel, begin to make their mark and professional interpreters agree with this fact. (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 11: Page 261)

First, I address the terminology used by Paul, ‘our gospel’. This is a term that Paul uses constantly, and although it appears quite innocent at this writing, later it takes on much greater significance. Of first note, it tells us that other gospels were being actively spread through this same territory.

Second, Paul says that this gospel, “…came to you not only in word, but also in power and in the Holy Spirit…” (1 Thessalonians 1:4; RSV)

Where did Paul receive this gift? It was not bestowed upon him by the Apostles, and most assuredly not by Jesus. He was not present at Pentecost. What we seem to have is Paul’s generalization of a very specific, physical act in which certain individuals are given the gifts of God’s Spirit. Paul uses it here to expound the authority of his gospel, but no ‘gift’ as is usual with this agency is in evidence.

Our professional interpreter’s have nothing to say about this oddity, which today, is in common use within the body of the church. It is expressed whenever any one wishes to impress others with the authority or importance of an act or statement, when no such power has actually been given. Paul obviously uses it in this context in his writing. Peake’s Commentary, however, seems to give reason to Paul’s writing, and we shall not leave their thoughts out. (Peake’s Commentary on the Bible; page 997: 870b)

The Greek text uses the term, pneumati agio, which is not indicative of the Holy Spirit himself, but of his gift. In this case, Paul considers his gospel to be a gift of the Spirit.

As a personal comment by this student, I would venture a word of caution. Those who comprise the body of the church today have adopted a very dangerous concept. It is, expressly, that no other spiritual power can possible evidence itself in the works of man in his ‘congregation’ other than God or His Holy Spirit. There is, however, another power that any sane individual must always take into account when pursuing matters that are beyond mortal concepts.

Jesus warned us of it in a most serious manner, but we have chosen to make light of that source of spiritual energy. Here, we note a comment of the translator’s that might best be taken with a grain of salt, for there is one power beyond all others save the Lord God of Hosts and His Holy Spirit, which can also lead man astray without his ever being aware of that interference. It is beyond foolishness to make jokes, or to wave aside as insignificant, an enemy that has the power to seduce and destroy us without effort.

To believe that we have the power to overcome that One, to laugh at that existence when one has never faced it flesh-to-flesh, breath-to-breath, and face-to- face is to invite certain disaster. In this instance, when the shadows are being lifted from the character of Paul for the first time, it would be best to reserve our judgment as to which power was leading the direction of the ‘church’ and the man.

When involved in mortal combat, it is always wise to know your enemy. In our case, we have chosen to ignore him. But it is time to continue with Paul’s letter.

“…Jesus who delivers us from the wrath to come.” (I Thessalonians 1:10; RSV)

Since Paul envisioned Jesus’ return in his own lifetime, it is likely that Paul also conceived of a ‘timeless’ savior (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 11: Page 265) who would deliver those who believed in him from the Day of Judgment, the Day of God’s wrath. Unfortunately, Jesus is reflected in Revelation as stating just the opposite.

“Behold, I am coming soon, bringing my recompense, to repay every one for what he has done.” (Revelation 22:12; RSV)

It is also interesting to note the problem that Paul had at Philippi. In this letter, Paul does not bother to explain what problems they had encountered. He simply states that they were, “…shamefully treated at Philippi, as you know…” (I Thessalonians 2:2)

However, if Luke is to be believed in this scenario, Paul’s quick temper and irritable nature provide the vehicle for their being put into prison. If Paul had such power, than this would be the only evidence of it in his entire ministry. Paul never mentions it, and might well have been embarrassed by the revelation of his uncalled-for deed.

“As we were going to the place of worship, we were met by a slave girl who had a spirit of divination and brought her owners much gain by soothsaying. She followed Paul and us, crying, “These men are servants of the Most High God, who proclaim to you the way of salvation.” And this she did for many days. But Paul was annoyed, and turned and said to the spirit, “I charge you in the name of Jesus Christ to come out of her.” And it came out that very hour.” (Acts 16:16-18; RSV)

“…’spirit of divination; literally ‘python’, a name derived from the serpent slain by Apollo at Delphi. Since the Delphic priestess was inspired to give oracles, a ‘python spirit’ meant a spirit of soothsaying.” (Peake’s Commentary on the Bible; page 911: 793 L) This statement is quoted here as a matter of definition, and nothing more.

The resulting outcry is not what concerns us here, it is the matter of Paul casting out a gift of the Spirit because it annoyed him. This ‘gift’, one of many that were manifest at Pentecost, and of which Paul spoke as being evidenced within the ‘church’ as the gift of prophecy, originally meaning, ‘foreseeing’, was surely given by the Holy Spirit, for it apparently proclaimed the authority of God and His Spirit. There is no conclusion made that it was an evil spirit.

The woman makes use of the title, “Most High God.” See, Luke 8:28 where, as here, it occurs in the utterance of a demoniac. It was used in syncretistic cults as a title for a supreme deity, being derived from Judaism. There is no reason to believe that this woman, or her owners, belonged to such a cult. (Peake’s Commentary on the Bible; Page 911: 793j)

The theologians attempt to convict the girl as a ‘demoniac’, but there is no such charge established or even hinted at by Paul or Luke. It is absolute rubbish to attempt a cover-up for this act of outright ‘vandalism’ with unauthenticated accusations. And if the truth be known, Paul himself was influenced by his Pharisaic education, his Hellenistic upbringing, and the pagan religions that influenced him and his times.

One must surely keep this negligent act in mind when evaluating the nature of the man. If this is truly the reason for their ‘shameful treatment. It was Paul who brought it on himself, and not those who resided in Philippi. And it was not caused by his preaching any gospel. Regardless of the spirit’s ‘residence’, or the owners’ profession, he had no right to do what he did, especially because he, “….was annoyed.”

Keep in mind that the gift of ‘prophecy’ is highly regarded by Paul. The powers of ‘divination’ and ‘soothsaying’, are no less than the gift of prophecy.

It is here that Paul makes his first claim to a questionable authority. It is a claim that will bring immediate and harsh response from those in the Jerusalem Church. The Twelve and the church elders, who are to remain Paul’s constant adversaries, are quick to respond to his outrageous claim.

“…nor did we seek glory from men, whether from you or from others, though we might have made demands as apostles of Christ.” (I Thessalonians 2:6; RSV)

Paul has grown in stature. From a mysterious vision near the Damascus Road, to being the bearer of ‘his’ gospel, to being “…approved by God…” (I Thessalonians 2:4; RSV) to being an apostle. The fact that this statement is openly challenged comes to light through Paul’s own written word, which we will investigate within this thesis.

The point here is that until that moment, the ‘Apostles’ were the ‘Twelve’, chosen by Jesus! Although this was fully discussed in, ‘In Defense of the Apostles Faith’, we must note that there can be no higher calling than to have been chosen by the Christ himself. This was not the case with Paul, who in an effort to begin casting the frame of a self-pronounced authority, reduces the meaning of ‘apostle’ to some lesser definition.

In this instance, he proceeds the term with, ‘WE’.. It is very shortly to become, ‘ME’. There is no explanation given by theologians or interpreter’s for Paul’s sudden use of the title except to apply it to himself whenever his name is mentioned. Yet, there is no evidence as to how he attained this position save by his own proclamation.

See: Peake’s Commentary on the Bible; Page 997: 870g

It is not clear if this statement by the theologians points toward the, Twelve, or Paul’s group. There is certainly no evidence that Paul or any of his following were commissioned by Christ as his apostles. But the modern church has gone Paul one better by proclaiming him to be, Saint Paul.

It is also stated that they are preaching, “…the gospel of God.” (I Thessalonians 2:9; RSV)

“And we also thank God constantly for this, that when you received the word of God which you heard from us, you accepted it not as the word of men, but as what it really is, the word of God…” (I Thessalonians 2:13; RSV)

This claim is to be extremely revealing in future correspondence. The statement becomes extraordinary later as Paul’s thinking becomes more telling and his battle against the Gospel preached by the Apostles, escalates. Paul is saying that the church is to take the gospel he preaches as the word of God Himself, not as a gospel preached by men. The authoritative tone is striking.

Paul then makes an all-condemning statement which, in later ages, the church takes up with a vengeance.

“…for you suffered the same things from your own countrymen as they did from the Jews, who killed both the Lord Jesus and the prophets, and drove us out…”

We have already learned that Paul was a Diaspora Jew, and one proud both of his heritage and his standing as a Pharisee. He would be whenever convenience demanded it. Now however, he turns on his own countrymen as he will later turn on all that he learned, “…at the feet of Gamaliel, educated according to the strict manner of the law of our fathers…” (Acts 22:3; RSV)

Paul’s words are even questioned by professional theologians who find his attitude severe, and unreconciled with his normal view of his fellow Jews. (Peake’s Commentary on the Bible; Page 998: 870h)

Even in this passage the theologian makes the daring statement that the Jews were guilty of the crime of crucifixion. I would remand all students and teachers alike to review the Gospel stories with great care.

The Jews as a people, and especially the Palestinian Jews, had nothing to do with seeking Jesus’ death. And although the Pharisees, the priesthood, sought to have him killed they did not crucify him and he was not put to death for any religious crime, i.e., heresy, apostasy, or sacrilege. It is in order to note, however, just how Paul’s ideas have filtered down to our modern minds.

Paul continues with this unhappy disposition. Giving voice concerning his previous plans to visit Thessalonica, possibly on more than one occasion, he tells us that he was deprived of that meeting, claiming that, “…Satan hindered us.”

This statement takes us back to the ease with which spiritual terminology flows off the lips of men, especially Paul, for it is highly questionable as to whether he faced that One in the flesh. It also brings an interesting statement from the Interpreter’s Bible.

Luke, in Acts 16:6 tells us that Paul is said to have been “forbidden by the Holy Spirit” to preach the word in Asia. According to Acts 16:7, when he wanted to go to Bithynia “the Spirit of Jesus did not allow them” (cf. I Cor. 16:9). Again, professional Christians question how Paul was able to determine whether it was Satan or the Spirit who changed his plans.

This writer is one who believes that the decision was made according to Paul’s mood and what he desired. If he wanted to do something and unfortunate circumstances prevented it, then it was Satan who plotted against him. If he languished about a journey, or was hesitant about doing something and decided against it, then the Holy Spirit had intervened on his behalf.

Paul was, in fact, much like the church today, users of words but less acquainted with the ‘spirituality’ of the thing than they would have us believe. Too many things are said for convenience sake rather than from a true knowledge of the entities involved. Claims are made about the Holy Spirit without a real experience with God’s Spirit. Claims are made about the Evil One without a factual confrontation with that being.

Paul’s letter has dealt with things past, and he recalls having sent Timothy to check on the community. Now he revels in the present with Timothy returned bringing good news. However, Paul’s communication gives evidence that someone is attempting to ‘undermine’ his work.

“…we sent Timothy, our brother and God’s servant in the gospel of Christ, to establish you in your faith and to exhort you, that no one be moved…” (I Thessalonians 2-3; RSV)

As was usual with Paul, terms that he uses are found nowhere else in the Greek scriptures. The words here mean, to be ‘deceived’ or ‘led astray’. This would seem to indicate that others might be at work to hinder Paul’s gospel. The scholars of, The Interpreter’s Bible, agree. (The Interpreter’s bible; Volume 11: Page 285)

“…for fear that somehow the tempter had tempted you and that our labor would be in vain.” (I Thessalonians 3:5)

Was Paul speaking of the Evil One, or some party who might believe that Paul’s gospel was not the correct gospel? This is a growing theme, not only in Paul’s mind, but also in his writings to the various churches. In this case, Peake’s believes that he is referring to Satan, but that One does not come to Paul as himself, but is reflected in Paul’s mind, “…in the person of the Jews who were trying to undo all the achievements of the campaign (cf 2:1-12).” (Peake’s Commentary on the Bible; Page 998: 871d)

We must keep in mind that the, Twelve, were Jews; that the Jerusalem Church, was the Judaic-Christian movement, and that Paul was preaching without a first hand knowledge of Jesus’ life actions or teachings. His gospel was coming from his interpretation of what he had heard from third parties via an oral tradition and not from an actual life experience.

We must also keep in mind that Jesus’ mission was a Palestinian movement, and a Galilean. Paul, being a Dispersion Jew, would not place the same definitions and values on religious matters as Jesus and the disciples did. This can be verified by the fact of their different views and dates of celebration of, The Passover.

We must continually remind ourselves that the misfortune experienced by the Thessalonian congregation was brought down on them by Paul. He has, however, once again escaped the pain and anguish that he has caused others. This time there appears to have been great anxiety on his part, perhaps from feelings of guilt.

Paul goes on to indicate that he and his associates had taught the Thessalonians how they, “…ought to live and please God, just as you are doing, you do so more and more.” (I Thessalonians 4:1)

He then goes on to outline what has already been instructed about immorality, marriage, and social behavior. But Paul does not include us in the particulars of these concepts and we are left to gather them from later writings. He does, however, leave us with a threat of God’s vengeance. “…for whoever disregards this, disregards not man but God, who gives his Holy Spirit to you.” (I Thessalonians 4:8; RSV)

It is indicative of Paul’s nature that he supports the authority of his teachings with a threat of violence that will be occasioned by The Almighty should anyone disregard his word. Quite obviously Paul believes that his instruction, his ‘word’, is the word of God, and to deviate from his instructions is to bring the wrath of God down on their heads. Having completed this part of the letter, Paul states his theology very clearly. His utmost expectation was that Jesus was going to return at any moment, without fail, during his lifetime.

“For since we believe that Jesus died and rose again, even so, through Jesus, God will bring with him those who have fallen asleep… And the dead in Christ will rise first; then we who are alive, who are left, shall be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air; and so we shall always be with the Lord.” (I Thessalonians: 4: 14-17; RSV)

As uncertain as any one else, Paul opens a part of the letter that would appear to be derived from Jesus teaching about the coming of the Kingdom. It is completely foreign to any of Jesus’ teachings about the Kingdom of Heaven, and in the Gospels, this parable has political overtones. Here, Paul uses it to refer to the return of, Jesus. Theologians and translators alike, however, have difficulty with this.

“You yourselves know well that the day of the Lord will come like a thief in the night.” (I Thessalonians 5:2; RSV)

As to Paul’s teaching on how to live, we have no indication as to how they came to this knowledge. It is the theologian’s belief that it is Paul’s teaching, as elsewhere in the letters to the Thessalonians, and not God’s. (The Interpreter’s Bible; Volume 11: Page 308)

In other words, this is probably Paul’s personal belief concerning the parousia. Even though it corresponds with the Gospels, as we have already pointed out, it is in a completely foreign context to that which Jesus was teaching. Paul continues with the very core of Christian belief, the sacrifice of Jesus’ life for our salvation.

“For God has not destined us for wrath, but to obtain salvation through our Lord Jesus Christ, who died for us so that whether we wake or sleep we might live with him.” (I Thessalonians 5:9-10)

The traditional act of the blood offering of a human sacrifice for the forgiveness of sins, is as ancient as man. It has appeared in every society at one time or another. It has eventually been replaced by a God of love and compassion who has forgiven those who follow His ordinances and attempt to lead a righteous life through the path He has chosen for them. This is true in every case, with the exception of Christianity.

This custom is propelled by Paul throughout his ministry and continues to be the very center of the Christian faith.

Paul ends the letter beseeching the Thessalonians to commit themselves to ‘righteous’ living and kindness to one another. In doing so, we must pay attention to his final admonition.

“Do not quench the Spirit, do not despise prophesying, but test everything; hold fast to what is good, abstain from every form of evil.” (I Thessalonians 5:19-22)

From the example we have of Paul’s actions in casting out the spirit of ‘divination’ in Acts, it might be proper to note that he is apparently asking his followers to, ‘Do what I say, not what I do.”

One other matter must be considered before we end this examination of 1 Thessalonians. Timothy has been referred to as being alone in Thessalonica. But as we are to learn, when Paul sent someone to ‘correct’ or ‘admonish’ a congregation, he never sent them without an escort of three or four of the ‘brothers’. This is to be proved later in our study, but for the moment, suspicion reigns.

Having already discussed the relevance of II Thessalonians, it would still be a good idea for the honest student to read through that epistle. The differences should be obvious to even the least informed reader, for in it, Jesus becomes the destroyer, (II Thessalonians 1:6-9) there is reference made to letters, “…purporting to be from us…”, (II Thessalonians 2:2) which indicates Paul’s growing paranoia concerning his teachings, i.e.; his gospel.

There is a tone of apocalyptic nature in the description of the ‘rebellion’, and a, ‘man of lawlessness, the son of perdition’. (II Thessalonians 2:3-4)

None of this is evidenced in any other of Paul’s writings. Aside from this, more perfect forms of the high Greek are used which are not a part of Paul’s usual writing style or ability. And professional Christian theologians agree that it is not of the Pauline corpus. For study’s sake, the reasons are repeated here. (Peake’s Commentary on the Bible; Page 996: 869e)

With this in mind, we move on to that which is usually considered Paul’s next letter, I Corinthians.